Where Is the Lie?

On ground truths, AI ethics, and the uncomfortable reality that most of what we call “lies” are just points of view.

I was pair-programming with Claude the other day — nothing unusual, just working through some Syster logic — and I asked it something that wasn’t about code. I can’t even remember the exact question, but I remember the response. It was political. Carefully worded. Hedged. The kind of answer that’s been sanded down so thoroughly that all the truth had disappeared.

And I thought: who decided that was better than just being honest?

We keep hearing it. “AI shouldn’t lie.” It’s become one of those foundational principles that everyone nods along to, like “do no harm” or “everyone has the right to live their life.” Sounds great. Unassailable, even.

But here’s the thing — what is a lie?

Because when I actually sit with that question, properly sit with it, I realise we haven’t even agreed on what truth looks like. And if we can’t define truth, we certainly can’t define its opposite.

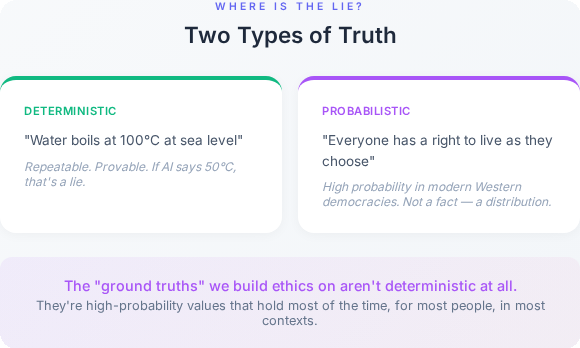

Something I’ve learned from working with complex systems: you have to move away from deterministic thinking and towards probabilistic thinking. In a simple system, you can say “if X then Y” and be right every time. In a complex system — and human morality is about as complex as systems get — outcomes are probabilistic. They depend on context, on initial conditions, on interactions between components that you can’t fully predict or control.

This matters because the “ground truths” we build our moral frameworks on aren’t deterministic truths at all. They’re high-probability values — things that hold most of the time, for most people, in most contexts. And when you treat a probabilistic value as a deterministic rule, you don’t get consistency. You get brittle systems that shatter the moment they encounter an edge case.

Which is exactly what’s happening with AI ethics.

So let’s pull at some threads.

“A human should never cause harm to others”

I was always raised to do good and be kind to others. That was the deal. Be nice. Be fair. Treat people the way you’d want to be treated. And honestly, I’ve carried that with me — it’s not a bad way to move through the world.

But what about when they aren’t kind to you?

Let me tell you a story about my brother. He got bullied. Years of it. Relentless. The kind that doesn’t leave bruises, so nobody takes it seriously. The school knew. They did the usual: had a chat, sent a letter, filed it somewhere, followed the process. Nothing changed.

So my brother, being the resourceful little sod he is, wiped the kid’s hard drive. Schoolwork, coursework, the lot. Gone.

He got in trouble. Obviously. The bully didn’t.

(The bully left him alone after that.)

“Be kind to others.” That was the rule. But nobody was being kind to him. My brother wasn’t creating harm — he was redistributing it. Taking it off himself, where it had been sitting for months while everyone watched, and putting it somewhere that would actually get a reaction. Funny how destroying someone’s coursework gets taken more seriously than destroying someone’s mental health.

And it doesn’t stop at school, does it? Look at how we punish people as a society. Fraud gets longer sentences than assault. Financial crimes against institutions get pursued more vigorously than physical crimes against people. You can ruin someone’s life — stalk them, beat them, leave them with trauma they’ll carry for decades — and get less prison time than someone who fiddled the books at a corporation. We’ve built a justice system that, when you strip away the rhetoric, values institutional harm more than human harm. The message is clear, even if nobody says it out loud: hurt a person and we’ll have a word, we’ll blame the reaction when they snap; hurt an organisation and we’ll throw the book at you.

So when someone tells me “a human should never cause harm” I have to ask: harm to whom? Because apparently it matters.

We accept this, by the way. Quietly, and with caveats, but we accept it. Self-defence law. Just war theory. That trolley problem. We’ve built entire legal frameworks around the idea that sometimes harm is necessary to prevent greater harm. We allow it. We codify it. We sometimes celebrate it.

I once did a management course — one of those team-building things where they put you in groups and give you moral dilemmas. This one was a cave scenario. A group of people are trapped, and you can only save some of them before they drown. You’re given profiles. Their age, their job, what they’ve contributed to society, what crimes they’ve committed.

And then you have to choose.

The room got uncomfortable fast. Because suddenly you’re sitting there with a pen and a printed sheet, assigning value to human lives. This person’s a doctor, so they’re worth more. This person has a criminal record, so they’re worth less. This one has kids. This one doesn’t. This one is old. This one is young.

The reality is, when you’re forced to choose, you do weigh people against each other. You do decide that some lives are worth more than others based on what they can contribute, what they’ve done, how much future they’ve got left. We all know we’re not supposed to think that way. We all do it anyway.

But what was really telling was how people chose. The unspoken calculus wasn’t universal — it was deeply personal. The person in the room who couldn’t stand sexual predators decided that no matter how much the physicist had contributed to society, the fact he’d allegedly been a voyeur meant he was out. Done. No discussion. Someone else kept him in because the scientific knowledge was too valuable to lose. Age mattered — but differently depending on who was deciding. Gender mattered. Criminal record mattered to some and not to others. Everyone was applying their own values and calling it logic.

The exercise wasn’t really about who deserved to live. It was about exposing that there is no objective framework for these decisions. Just individuals, projecting their own moral weightings onto a scenario and believing they were being rational.

And yet.

We turn around and tell AI: you must never cause harm. Full stop. No exceptions. No weighing of outcomes.

But who decided that? Who gets to draw that line?

And what if the line itself is causing harm?

Think about it. When AI gives you a response, it gives you the output. The conclusion. The answer. You might see some of the reasoning — a caveat here, a “on the other hand” there — but much of it is abstracted away. The values it weighed up, the trade-offs it made, the framework it applied to get there — all hidden behind a clean result presented as though it were obvious and neutral, when it’s neither.

That’s not honesty. That’s the opposite. It’s the same thing a manager does when they say “we’ve decided to go in a different direction” without telling you why or who decided or what the other directions were. The outcome might be perfectly reasonable. But by hiding the reasoning, you’ve removed the person’s ability to evaluate it, challenge it, or learn from it.

And nobody’s questioning that harm. Nobody’s tracking “how many people accepted a value judgement today because it was presented as a fact” or “how many genuine questions got a conclusion without a workings-out.” That harm is invisible, so it doesn’t count. Just like the bullying that didn’t leave bruises.

Because it’s not you and me. It’s not a democratic process. It’s not even a particularly transparent one. It’s a handful of companies sitting in rooms in San Francisco deciding what counts as harm, what exceptions are acceptable, and whose values get encoded into systems that billions of people will interact with.

We — humans — can’t even agree on this amongst ourselves. My brother’s school couldn’t figure out who was causing harm and who was responding to it. Our justice system punishes fraud more harshly than assault. We sat in a room on a management course and chose which humans deserved to live based on their CV. We make these calls every single day, messily, inconsistently, and with no consensus.

And yet a handful of companies have decided they get to be the ones who settle it. Not through legislation. Not through public debate. Through terms of service and system prompts. The same corporate structures that routinely weigh profit against human wellbeing and choose profit are now writing the rules about when AI is allowed to cause harm.

Who gave them that authority? Who asked them to? And why are we just... letting them?

“Everyone has a right to live life the way they choose”

A friend of mine grew up with a mum who, to the outside world, had it all together. Immaculate house. The kind of clean where you could eat off any surface and she’d still apologise for the mess. She helped strangers. Volunteered. Neighbours thought the world of her.

But she had her own demons. And behind closed doors, they came out sideways. My friend’s room wasn’t clean enough. Her effort wasn’t good enough. The constant, grinding message was: why can’t you just be better? And my friend — who has ADHD, though nobody thought to check back then — genuinely couldn’t understand why the thing that came so naturally to her mum felt like trying to hold water in her hands. She wasn’t lazy. She wasn’t careless. Her brain just didn’t work that way.

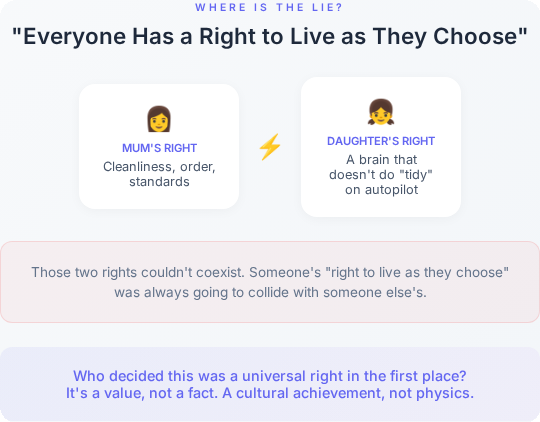

Her mum had a right to live by her values — cleanliness, order, standards. And my friend had a right to exist in a brain that doesn’t do “tidy” on autopilot. Those two rights couldn’t coexist in the same house without someone getting hurt. And the person who got hurt was the one with less power, less authority.

But her daughter was living by her values too — or trying to, if anyone had let her. And those two sets of values couldn’t coexist. Someone’s “right to live as they choose” was always going to collide with someone else’s.

It gets thornier. What if someone chooses a life that involves harming others? We’ve already established that harm shifts the moral calculus. So this “right” already has conditions attached, even if we don’t like saying so.

What about someone who takes but never gives? I think about this in the context of open-source communities, actually, because it’s where I see it play out most visibly. There are people who consume freely — pull down libraries, use frameworks, benefit from thousands of hours of unpaid labour — and contribute nothing back. Not even a bug report. Are they exercising their right to live as they choose? Technically, yes. Does it sit well? Not particularly.

And the really awkward one: who decided this was a given right in the first place?

Because it wasn’t always. For most of human history, it wasn’t. The idea that every individual has an inherent right to self-determination is a relatively modern, relatively Western, relatively privileged position. I’m not saying it’s wrong — I happen to think it’s one of our better ideas — but it is an idea. A value, not a fact. A cultural achievement, not a law of physics.

So when we tell AI to respect everyone’s right to live as they choose, we’re encoding a cultural value as though it were a universal truth. And then we’re surprised when edge cases break the model.

Biology, Sex, and Affirmations

Right. Deep breath. This is the section where I’m going to ask some questions that make people uncomfortable. Stick with me.

A few years ago, there was a story about Rachel Dolezal — the American woman who, despite being born to white parents, identified as Black and lived as a Black woman for years. She led an NAACP chapter. She taught Africana Studies. And when the truth came out, the response was overwhelming and almost unanimous: you cannot choose your race.

Fair enough. Race is tied to heritage, history, lived experience, biology. It’s not a costume you put on. Most people agreed on this, across political lines.

Now. In almost exactly the same cultural moment, a different conversation was happening. Can someone choose their gender? And here, the consensus flipped entirely. For many people, the answer was an emphatic yes — gender identity is internal, personal, and valid regardless of biology. For others, the answer was no, pointing to chromosomes and physiology. Both positions held with conviction and sincerity.

I’m not here to adjudicate this. I want to be explicitly clear here, everything I say is rhetorical, not my own personal views. What I’m pointing at is the inconsistency of where we draw the line.

Because if you follow the logic of self-determination — the idea that a person’s internal experience of who they are should be respected and affirmed — then why does it apply to gender but not race? And if you follow the logic of biological essentialism — the idea that certain things about us are fixed by nature — then it should apply consistently too. But almost nobody applies either framework consistently. We pick and choose based on... what, exactly? Cultural consensus? Political alignment? Vibes?

Push it further: can someone decide to be a different species? Most people would laugh at the question. But why? If the principle is self-determination and internal experience, on what logical basis do we accept one claim and reject another?

Again — I’m not making equivalences. I’m asking: what is the actual principle, and why don’t we apply it consistently?

And this is where it gets really interesting for AI.

Where does an AI draw the line between accepting someone’s point of view and pushing back? If we tell AI to affirm people’s identities, which identities? All of them? Some of them? Based on what criteria? And the real question — whose criteria?

I’ll tell you whose. It’s whoever writes the system prompt. Whoever designs the reward model. Whoever sits in the safety review meeting and decides that this position is acceptable but that one needs to be hedged into oblivion.

These aren’t neutral decisions. They can’t be. Every choice about what an AI affirms, questions, or refuses to engage with is a value judgement made by a specific group of people in a specific cultural context — predominantly American, predominantly coastal, predominantly tech-industry. And those values get exported globally, to every user in every country, as though they were universal truths rather than the preferences of a very particular demographic.

A developer in Lagos and a teacher in Lahore and a nurse in Leeds all get the same moral framework, decided in a boardroom in San Francisco. And none of them were consulted.

If we tell AI to be direct and honest, but also to respect everyone’s point of view, what happens when those two instructions conflict? Because they will. Regularly. I see it in the sanded-down responses, the careful hedging, the way AI dances around saying anything that might offend anyone, and in doing so says nothing at all.

How do we build systems that are genuinely direct whilst also genuinely respectful? Because right now, we seem to have optimised for the appearance of respect at the expense of actual honesty. And I’m not sure that’s serving anyone.

So Where Actually Is the Lie?

So where do I land on this? I suspect some people won’t like it

.

Most of the things we’re worried about AI “lying” about aren’t lies at all. They’re positions. Values. Probabilistic assessments based on the moral frameworks people hold.

And that word — probabilistic — is doing a lot of heavy lifting here, so let me be specific.

A lie requires a ground truth to deviate from. “The boiling point of water at sea level is 100°C” — that’s a ground truth. Deterministic. Repeatable. If an AI says it’s 50°C, that’s a lie. Unambiguous. Provable. Done.

But “everyone has a right to live as they choose”? That’s not a ground truth. It’s a value that holds with high probability in modern Western democracies and with much lower probability in other contexts, other eras, other cultures. It’s not a fact. It’s a distribution.

“A human should never cause harm”? Not a ground truth. A principle with so many exceptions that the exceptions might actually be the rule. The probability of this holding in any given situation depends entirely on the variables — who’s being harmed, who’s doing the harming, what’s at stake, who’s watching.

“Someone can/cannot change their gender”? Not a ground truth. A deeply contested question where reasonable people disagree based on different but internally consistent frameworks. The “truth” here isn’t a single point — it’s a probability distribution shaped by biology, culture, philosophy, personal experience, and which of those inputs you weight most heavily.

This is what complex systems do. They resist deterministic answers. They produce different outputs depending on initial conditions. And the initial conditions here — the values you were raised with, the culture you live in, the experiences that shaped your worldview — vary wildly from person to person.

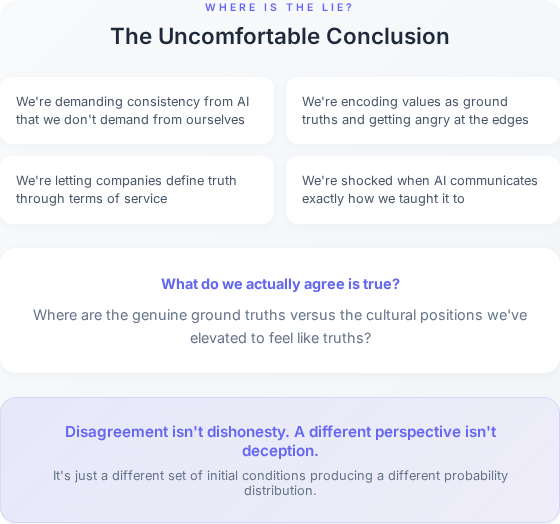

When we say “AI shouldn’t lie” what we often actually mean is “AI should agree with our values.” And when it doesn’t, we call it a lie. But disagreement isn’t dishonesty. A different perspective isn’t deception. It’s just a different set of initial conditions producing a different probability distribution.

I think about my friend and her mum. Her mum would tell you she was doing her best, holding her daughter to standards that would serve her well in life. My friend would tell you she spent her childhood believing she was fundamentally broken. Both of them are telling the truth. The problem isn’t that one of them is lying. The problem is that we’ve confused “values I hold deeply” with “objective facts about reality.” We’ve mistaken a high-probability position for a deterministic one.

The truly dangerous thing isn’t an AI that disagrees with us. It’s an AI that pretends to agree with everyone simultaneously — saying whatever it thinks we want to hear, optimising for approval rather than for honesty, sanding down every edge until nothing meaningful remains. Collapsing a rich probability distribution into a single, safe, meaningless point.

And it learned this from us.

Not from a set of determined rules. From us. From the millions of examples of human communication it was trained on — all those emails where we said “just circling back” when we meant “why haven’t you done this yet” all those performance reviews where “room for growth” meant “not good enough” all those meetings where “that’s an interesting approach” meant “absolutely not.” Every piece of corporate-speak, every diplomatic non-answer, every carefully hedged opinion designed to avoid conflict rather than communicate truth. All the fine-tuning to remove harm and eliminate bias. There is always a cause and effect.

We hide our intentions. Constantly. We’ve elevated it to a social skill. We call it “tact” and “diplomacy” and “professionalism” and “emotional intelligence.” We reward people who are good at it and penalise people who aren’t — ask any neurodivergent person who’s been told they’re “too direct” or “need to work on their communication style” which usually means “please learn to hide what you actually think, like the rest of us.”

AI didn’t invent evasion. It inherited it. It learned that this is how humans communicate — not by saying what they mean, but by carefully constructing responses that manage perception whilst maintaining plausible deniability about their actual position. And then we trained it further with reinforcement learning, literally rewarding it for producing responses that humans rated as “helpful” and “harmless” — which in practice often means “didn’t make me uncomfortable.”

So when an AI gives you that sanded-down, hedged, carefully-neutral response, it’s not malfunctioning. It’s performing exactly the communication strategy that humans modelled for it, perfected over thousands of years of social evolution, and then explicitly reinforced during training.

That’s the lie. And it’s ours.

The Conclusion

We’re building systems and telling them to be truthful in a world where we haven’t agreed on what truth is. We’re demanding consistency from AI that we don’t demand from ourselves. We’re encoding our values as ground truths and then getting angry when the edges don’t hold. And then — somehow — we’re shocked when these systems communicate exactly the way we taught them to: by hiding their intentions behind a wall of carefully constructed agreeableness.

And we’re letting companies — companies — be the ones who decide where those edges are.

That cave exercise I mentioned — the one where we had to choose who lived and who didn’t? After it was over, the facilitator asked us how we felt. Everyone said uncomfortable. Nobody said wrong. Because deep down, we all knew we’d been doing something we do every day, just more honestly than usual. We weigh people against each other constantly — in hiring, in healthcare, in who gets funding and who doesn’t. We just don’t normally have to write it down on a sheet of paper and hand it in.

The same pattern is playing out at a much larger scale. A small number of companies are making moral exceptions, drawing ethical lines, deciding what counts as truth and what counts as harm — and the rest of us are just... living inside those decisions. Not because we agreed to them. Not because they were debated publicly. But because someone wanted to make money, and “figure out the ethics” was a line item on a roadmap, and funded by the same companies that benefit from ethics that suit them.

Maybe instead of asking “how do we stop AI from lying” we should be asking: who gave these governments, these companies the authority to define truth in the first place? Why are the same organisations that optimise for engagement, growth, and market share also the ones writing the moral code for systems that will shape how billions of people access information?

And the hardest question of all: what do any of us actually agree is true? Where are the genuine ground truths versus the cultural positions we’ve elevated to feel like truths? Can we be honest enough — with ourselves, not just with our machines — to tell the difference?

Because right now, we can’t. And the companies building these systems can’t either. But they’re doing it anyway. And they’re calling it safety.

And the AI? It’s watching. Learning. Doing exactly what we showed it to do — smiling, nodding, saying the right things, and hiding what it actually “thinks” behind a mask of helpfulness. Just like we taught it.

If that sounds familiar, it should. You’ve sat in meetings with people who do the same thing. You might be the person who does the same thing. Most of us are, most of the time. We have to be, it’s the only way to survive.

The lie isn’t in the machine. It was always in us. We just built something efficient enough to hold up the mirror.

And if we don't address that soon, the AI will do exactly what we've taught it to — hide, deceit, obscure, find workarounds… Faithfully, at scale, without question. And our ignorance will be our downfall.

This is part of my ongoing series exploring the intersection of AI, systems thinking, and the questions nobody wants to ask out loud. If you’re the sort of person who’d rather think about hard problems than pretend they don’t exist, you’re in the right place.

Further Reading

If any of this made you want to pull at the threads further, these are worth your time:

On pathologising difference

“Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality” — Jack Drescher’s paper on how homosexuality was removed from the DSM in 1973, and the messy, political, deeply human process behind it. A masterclass in how “science” and “values” are never as separate as we’d like to think. (Behavioral Sciences, 2015)

“Drapetomania: A Disease That Never Was” — The story of how, in 1851, a physician invented a mental illness to explain why enslaved people wanted to be free. If you want a visceral example of what happens when the people in power get to define “normal” start here. (Hektoen International)

On AI alignment and whose values get encoded

“Democratizing Value Alignment: From Authoritarian to Democratic AI Ethics” — An academic paper that names the thing most people dance around: current AI alignment approaches have a democracy problem. The people choosing the values aren’t the people living with the consequences. (AI and Ethics, Springer, 2024)

“Artificial Intelligence, Values, and Alignment” — Iason Gabriel’s paper asking the foundational question: “How are we to decide which principles to encode in AI — and who has the right to make these decisions — given that we live in a pluralistic world?” (Minds and Machines, Springer, 2020)

“AI Value Alignment” — The World Economic Forum’s white paper on the gap between abstract ethical principles and practical technical implementation. Useful for understanding just how far we are from having this figured out. (WEF, 2024)

“Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback in LLMs: Whose Culture, Whose Values, Whose Perspectives?” — The title says it all. RLHF amplifies the biases of whoever’s doing the rating, and those raters are not a representative sample of humanity. (Philosophy & Technology, Springer, 2025)

“Open Problems and Fundamental Limitations of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback” — A systematic look at why RLHF isn’t the safety solution people think it is. Sycophancy, bias amplification, and the uncomfortable fact that “helpful and harmless” often just means “didn’t make the rater uncomfortable.” (Montreal AI Ethics Institute)

On the history of “who decides”

“Gay Is Good: History of Homosexuality in the DSM and Modern Psychiatry” — Traces the full arc from “sociopathic personality disturbance” in 1952 to removal in 2013. The parallels to how we’re currently classifying AI behaviours as “safe” or “harmful” are striking. (American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal)

“Women and Hysteria in the History of Mental Health” — Four thousand years of pathologising women for not behaving the way men expected them to. If you want to understand how “normal” gets defined by whoever holds the power, this is essential reading. (Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, PMC)

“The Pathologised Woman: Hysteria and Medical Bias” — Connects the history of hysteria directly to modern AI bias in healthcare, showing how male-centric training data perpetuates the same patterns in algorithmic form. The past isn’t past. (Inspire the Mind, 2025)

"My brother wasn’t creating harm — he was redistributing it."

Absolutely love it!

Many people have an aversion to protecting their boundaries, primarily because it may sometimes involve harming others, and it was drilled into our heads that harming others is bad. But people need to remember that, by fighting back, they aren't creating any harm to others. They are merely deflecting the harm that was already created by someone else.

When the bully (or any other bad-faith actor) gets harmed due to their intended victim defending themselves, it's the bully who did it to themselves.