The Linear Trap: How Western Culture Actively Prevents Systems Thinking

How We Educated, Organised, and Incentivised Ourselves Out of Systems Thinking

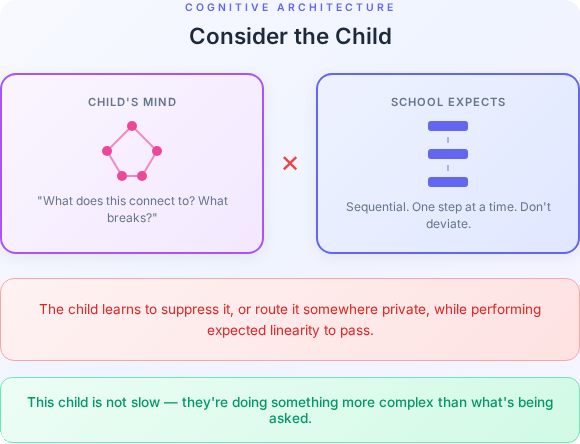

Consider a child who, when given a new concept, doesn’t process it and move on, but immediately starts asking what it connects to. What it breaks. What happens if you change one of the assumptions. What the boundary conditions are. This child is not slow. This child is doing something more complex than what’s being asked of them.

But the classroom is not built for that. The lesson has a sequence. The assessment has a format. There are twenty-eight other children and a curriculum that does not pause. So the child learns, quickly, that this kind of thinking — the reaching outward, the questioning of frames, the instinct to find the system before accepting the rule — is not what school is for. They learn to suppress it, or to route it somewhere private, or to perform the expected linearity well enough to pass while the real thinking happens underneath, untrained, unacknowledged.

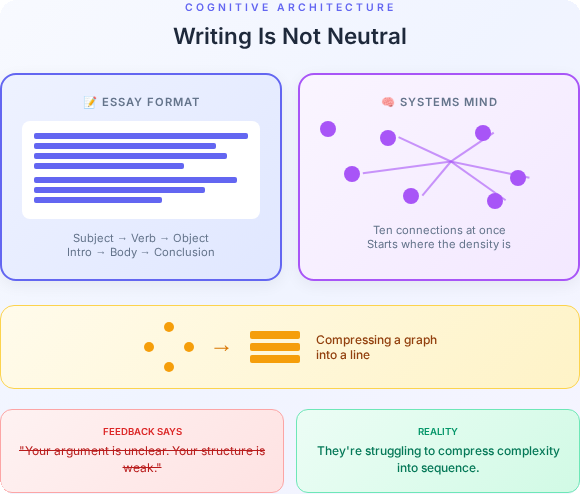

Consider also the medium through which almost all of this learning is delivered and assessed: writing. Western script runs left to right, top to bottom. A sentence has a subject, a verb, an object. A paragraph has a topic sentence, supporting evidence, a conclusion. An essay has an introduction, a body, a closing argument. Each element follows from the last. The structure is sequential by design, and it is treated not as one possible way of organising thought but as thought itself — the correct externalisation of a mind working properly.

This is worth sitting with. Writing is not neutral. It is a technology with a particular shape, and that shape encodes assumptions about how ideas relate to each other: one after another, causally, with a beginning and an end. A mind that naturally thinks in webs — that sees ten connections simultaneously, that wants to start in the middle because the middle is where the density is, that finds the idea of a single “conclusion” reductive because the system doesn’t conclude, it continues — is not well served by this format. Not because the ideas are unclear, but because the format cannot carry them without distorting them.

The child who struggles to write a linear essay is not necessarily struggling to think. They may be struggling to compress a graph into a line. But the assessment does not distinguish between these. The feedback is: your argument is unclear. Your structure is weak. You haven’t made your point. The implicit diagnosis is cognitive deficit. The actual problem may be cognitive mismatch — a mind that holds complexity simultaneously being asked to express it sequentially, and losing something essential in the translation.

This is where the conditioning begins. Not with malice, not through any single policy or decision, but through the accumulated pressure of a structure that has one mode and rewards those who match it. The system has a pace. The system has a shape. And that shape is linear — in its curriculum, in its assessment, and in the very medium it uses to determine whether you can think at all.

It doesn’t end at school. The same pattern recurs in every institution the child will eventually enter. A structure built for sequential processing, encountering a mind that thinks in networks — and the structure winning, because structures always do.

There’s a particular kind of conversation I’ve had many times throughout my career. Someone presents a plan, a product, a process. I start asking questions — not the surface questions, but the ones about what feeds into it, what it affects, where it breaks under load, how it interacts with the systems around it. And something shifts in the room. The questions read as obstruction. As arrogance. As chaos.

The plan was a list. My questions were a graph. And the problem isn’t that we disagreed — it’s that we weren’t even having the same kind of conversation.

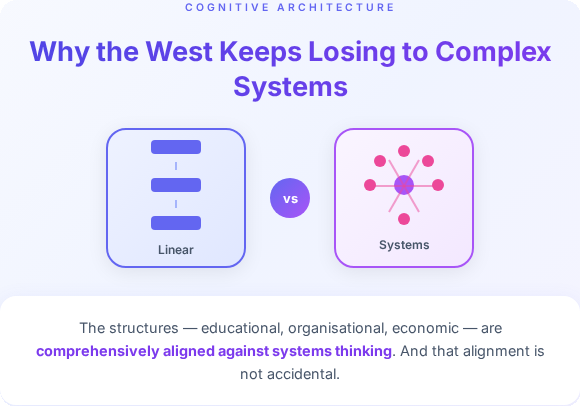

This is not a story about intelligence. The people in those rooms were often brilliant, experienced, capable. And neither is it purely a personal story — though the personal experience of it is real and cumulative. The problem runs deeper than individual friction. Western culture — through its institutions, its spoken language, its economic structures, its pedagogical traditions, and its built environments — doesn’t just fail to teach systems thinking. It actively constructs conditions that make systems thinking invisible, non-viable, and pathological. And the cruelest part: it can’t see this, because the blindness is the structure itself.

The Chain, Not the Web

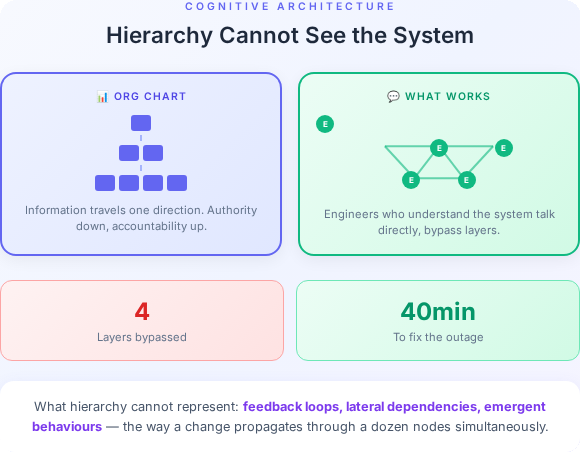

Start with hierarchy. It’s so embedded in how Western organisations function that we rarely examine it as a choice — it feels more like gravity. Org charts. Reporting lines. Approval chains. One decision-maker at the top, decomposed into delegations below.

Hierarchy is a linear structure. Information travels in one direction at a time. Authority flows down; accountability flows up. What it cannot natively represent is the actual topology of real systems: feedback loops, lateral dependencies, emergent behaviours, the way a change in one node propagates through a dozen others simultaneously.

When you try to operate a genuinely complex system inside a hierarchy, you have two choices: you can flatten the complexity (pretend the system is simpler than it is) or you can create informal networks that carry the real information around the hierarchy. Most organisations do both, and then wonder why things keep going wrong. The hierarchy gives them the illusion of control. The informal networks are what actually works. Neither is visible in the org chart.

Take incident response in a large software organisation. The org chart says: engineer escalates to team lead, team lead escalates to VP of Engineering, VP coordinates with Security and Infrastructure heads. That is the official topology. What actually happens during a critical outage is a Slack channel or a call where the three engineers who actually understand how the system is wired talk directly to each other, bypassing four layers of management, and fix it in forty minutes. The hierarchy is not wrong to exist — coordination at scale needs structure. But the structure didn’t solve the problem. The informal network did. And because that network is invisible, it is never invested in, never documented, and when one of those three engineers leaves, the organisation discovers it has lost something it didn’t know it had.

Or take a large government infrastructure programme — the kind that runs for a decade, costs billions, and involves dozens of contractors. The official hierarchy has a programme director, workstream leads, delivery partners, and governance boards producing reports at each level. The reports are accurate, in the sense that they represent what each node knows about its own part. What they cannot represent is how the parts interact — the dependency between the identity system and the payments system that neither team owns, the integration risk that lives in the gap between two contracts, the assumption baked into workstream three that workstream seven has not been told about. That knowledge exists, scattered across the people doing the work, carried in conversations and email threads and the institutional memory of whoever has been on the programme long enough to have seen it break before. It is never surfaced in the governance structure because the governance structure is not designed to ask for it. It asks for status. It gets status. The risk accumulates in the gaps.

This isn’t incidental. It’s load-bearing. Hierarchy produces accountability structures that reward the appearance of control over actual systemic understanding. The manager who can show a clean set of metrics beats the engineer who understands why those metrics are measuring the wrong thing. Systems thinking, in a hierarchy, is structurally punished — it produces uncertainty, questions, and demands for redesign, where the hierarchy needs confidence, answers, and stability.

Centralised or Fragmented — Never Systemic

Look at how infrastructure is built and owned in the West and you see the same pattern at scale, expressed in two modes that look like opposites but produce the same failure.

The first mode is fragmentation. Infrastructure built in pieces, owned by competing interests, stitched together at the edges. Transport networks that don’t talk to each other. Digital identity systems that don’t interoperate. Healthcare data locked in incompatible silos. Every actor optimises for their own node. Nobody owns the topology. The system as a whole is nobody’s responsibility, because the system as a whole was never anybody’s design.

The second mode is centralisation. A single platform, a single vendor, a single authoritative source — but one that is opaque, unmodifiable, and understood only by those who built it. The complexity hasn’t gone away; it’s just been hidden behind an interface. Dependency replaces understanding. When something breaks, nobody inside the organisation knows why, because knowledge of how the thing actually works was never theirs to begin with.

Neither mode produces systemic knowledge. Fragmentation distributes ignorance across nodes. Centralisation concentrates it behind a wall. What both have in common is that the people operating the system cannot see it whole — and over time, stop expecting to.

This shapes cognition directly. The tools you build with shape the problems you can see. When your working environment is either a collection of disconnected point solutions or a black-box platform you can’t inspect, you get very good at one thing: working within constraints you cannot change. You become expert at the seam, the workaround, the integration layer. What you do not develop is fluency in designing systems whole, because your environment has never asked that of you.

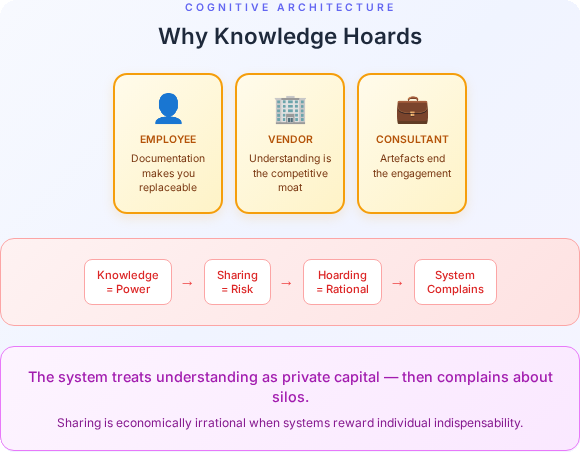

Here’s where the knowledge question becomes inseparable from the infrastructure question. In both fragmented and centralised systems, systemic knowledge — understanding of how the whole thing actually works — accumulates in very few places, and those places guard it. Not always consciously. Often structurally. If you understand how something works and nobody else does, that understanding is power. It determines your irreplaceability. It shapes your position in the hierarchy. Sharing it, documenting it, making it legible — these are economically irrational acts in systems that reward individual indispensability over collective capability.

So knowledge hoards. Not because people are uniquely selfish, but because the system treats understanding as private capital and then complains about silos. The person who knows how the legacy system works doesn’t write it down because writing it down makes them replaceable. The vendor who understands the platform keeps that understanding proprietary because it is their moat. The consultant who maps the organisation’s processes doesn’t leave a permanent artefact because the artefact would end the engagement.

This is why building and automating workflows at scale is so persistently hard — not as a tooling problem, but as a knowledge problem. Every automation attempt begins with archaeology: reverse-engineering what the system actually does rather than what anyone designed it to do, because the design was never shared, never documented, or was documented once and immediately fell out of date. The mental model required to see a workflow as a graph — with inputs, outputs, failure modes, and feedback — exists somewhere, in someone’s head, but it was never made into infrastructure. It was kept as leverage.

The alternative — distributed, accessible, federated knowledge — requires a fundamentally different arrangement. It requires that the system’s capability matters more than any individual’s position within it. Decentralised, commons-based structures — open source, open standards, federated architectures — are the technical embodiments of that philosophy. It is not a coincidence that they remain perpetually under-resourced relative to their importance, or that the organisations that extract the most value from open source are frequently the ones least likely to contribute back to it.

Capitalism, Consumerism, and the Abstraction Hierarchy

There’s a particular kind of systems thinking that is valued and well-resourced in the West. Strategic analysis. Enterprise architecture. Consultancy. The kind of thinking that happens at the top of the abstraction hierarchy, far from implementation.

This isn’t accidental either. Capitalism doesn’t discourage abstraction — it commodifies it. The abstraction layer becomes the product. Complexity below is hidden from the consumer; the interface is clean, simple, frictionless. This is good product design in many respects. But it also creates a cultural relationship with technology (and with systems generally) that is fundamentally passive.

The consumer is not supposed to understand the system. Understanding is not the product. The product is the outcome, the deliverable, the interface. Systems thinking — real systems thinking, which requires engaging with complexity rather than being protected from it — becomes the exclusive province of a specialist class. Everyone else learns to operate pre-built abstractions.

This produces a particular kind of elitism around systems thinking, and I want to be precise about how it works: it’s not that systems thinkers are elitist. It’s that the economic structure turns the ability to engage with complexity into a differentiating credential, because access to that complexity has been deliberately gated. The abstraction layer isn’t neutral. It’s a boundary of participation.

Consumerism trains people to receive systems, not design them. And systems that can only be received, not modified or understood, cannot be democratically governed. This is not an accident.

What the System Is Actually Producing

The childhood experience I described isn’t a side effect of education. It’s the output.

Formal education in the West is predominantly linear and sequential by design. You learn topic A, then topic B, then topic C. Each builds on the last. The curriculum is a chain. Assessment is point-in-time. Knowledge domains are siloed by subject, department, timetable. This is a structural choice with structural consequences: it trains a particular cognitive habit — read the material, understand it in isolation, reproduce it on demand.

It does not train the habits of systems thinking: hold multiple things in relation simultaneously, look for feedback loops, ask what happens at the boundaries, consider the system under different conditions and timescales. Those habits, when children exhibit them naturally, get managed rather than cultivated. The lesson has to move on.

What the educational system produces, at scale, is populations of people who are capable within a domain — literate, numerate, skilled — but who have been trained out of the instinct to ask “what is this connected to, and what does the connection do?” They are trained to operate the system, not to see it.

None of this is to say that linear thinking is without value. It has real and significant strengths. Tenacity — the capacity to go deep into a difficult domain, to stay with a problem until it yields — is a linear virtue. Rigorous sequential reasoning, the kind that produces reliable research, precise engineering, and careful scholarship, depends on it. Top-down thinking, the ability to decompose a complex problem into tractable pieces and work through them methodically, is genuinely powerful. These are not weaknesses dressed up as strengths. They are real capabilities, and the people who have them well-developed are capable of things that purely associative, networked thinking struggles with.

The danger is not linear thinking. The danger is treating it as the only legitimate mode, at every stage, from childhood onwards. Top-down decomposition without bottom-up synthesis produces systems that are locally coherent and globally broken. Tenacity without the capacity to question the frame produces experts who dig very efficiently in the wrong place. Research depth without systems breadth produces knowledge that cannot be integrated or applied across domains.

Both modes are necessary. What’s missing is not linear thinking — it’s the deliberate cultivation of both from the beginning, the understanding that different problems require different cognitive approaches, and the institutional tolerance for people who naturally lead with one mode or the other. Instead, we select for one and route the other out.

The question I keep returning to is: is this a bug or a feature? Systems thinkers are uncomfortable in hierarchies. They ask inconvenient questions. They identify structural problems rather than accepting the system as given. They resist the kind of compliance that institutional structures depend on. A population systematically educated away from systems thinking is also a population that is easier to manage, easier to sell to, and less likely to organise around structural critique.

I am not making a conspiracy argument. I am making a structural argument: these outcomes are entirely consistent with the incentives of the institutions that shape education, even if nobody planned them.

The Pathologising of Difference

Which brings me to what I think is the most quietly devastating part of this story.

Linear structures don’t just prefer linear thinking. They pathologise the alternatives.

In a hierarchy, the person who sees the whole system rather than their part of it is difficult. Insubordinate. Not a team player. Unfocused. In an educational system built on sequential processing, the person who learns associatively, spatially, through pattern recognition and parallel processing doesn’t fit the assessment structure — and gets labelled accordingly. Distracted. Disorganised. Struggling.

Many of the cognitive profiles we now associate with neurodivergence — ADHD, autism, dyslexia — involve precisely the kinds of thinking that linear structures struggle to accommodate and systems thinking rewards: high pattern recognition, sensitivity to context and environment, tendency to think in networks rather than sequences, discomfort with arbitrary rules in the absence of underlying logic. These are not deficits in any neutral sense. They are deficits relative to a particular structural expectation.

The pathologising is real. The suffering is real. I am not minimising that. But the framing — that the individual is the problem — systematically obscures the structural question: what would it look like to build institutions around a wider range of cognitive architectures? What do we lose by filtering these thinking styles out?

We lose, among other things, a lot of the people who are most capable of seeing systems as systems. This is not the only cost, but it is a significant one when we’re trying to understand why organisations, economies, and societies repeatedly fail to manage complex systems well.

The Pattern the West Keeps Losing

There is a version of this argument that plays out not just within Western institutions but between them and the rest of the world — and it follows a remarkably consistent sequence.

Western research centralises. The model is the university lab, the corporate R&D division, the national research council. Funding flows to named investigators with defined specialisms. Intellectual property is protected from the moment of creation — patents filed before publication, NDAs before collaboration, licensing agreements before deployment. The outputs are papers, patents, and proprietary methods, each owned by an institution, each measured in isolation. This produces genuine depth. Bell Labs invented the transistor. DARPA built the foundations of the internet. Western pharmaceutical research has produced treatments that have saved hundreds of millions of lives. The depth is real.

But depth is not the same as capability at scale. The transistor took decades to move from Bell Labs to a functioning consumer electronics industry — and that industry was not built in America. The internet’s physical infrastructure, the devices that run it, the manufacturing processes that make those devices economical — almost none of that was developed or retained in the West. The research happened here. The systemic capability to build on top of it, to integrate it into supply chains, to iterate on it across thousands of interdependent processes — that happened elsewhere. Western research produced the seed. The capacity to grow it at scale was built somewhere else, using a different model.

Part of why is structural, and it runs deeper than simple offshoring. Western economies do not reward the building of foundations. They reward the control of bottlenecks. A foundation — shared infrastructure, common standards, a manufacturing capability that the whole ecosystem can build on — is economically unattractive precisely because it is hard to own. It accrues value to the system rather than to the entity that built it. A bottleneck, by contrast, is enormously valuable: a chokepoint in a supply chain, a proprietary interface that competitors must licence, a platform that extracts rent from every transaction that passes through it. The incentive is not to build the thing the system needs. The incentive is to find the point in the system where dependency can be manufactured and held.

This is why Western technology strategy has consistently produced platforms rather than infrastructure, APIs rather than open standards, subscription lock-in rather than owned capability. Each of these is a bottleneck masquerading as a product. And each one makes the underlying system more fragile — more dependent on a single point, less able to adapt when that point fails or changes its terms. The COVID supply chain crisis was not an anomaly. It was the logical outcome of decades of optimising for bottleneck control rather than systemic resilience, of treating just-in-time delivery as efficiency rather than recognising it as the elimination of slack that complex systems need to absorb disruption. The foundations had been quietly hollowed out. Nobody noticed until they were needed.

Eastern industrial culture systemises. The clearest examples are Japanese manufacturing from the 1960s onward, the South Korean chaebol model of the 1970s and 80s, Taiwan’s semiconductor ecosystem built around TSMC from the 1980s to today, and China’s industrial expansion from the 1990s onward — first as assembler, then as manufacturer, now increasingly as innovator. These are not identical — their structures, state relationships, and timescales differ significantly — but they share an orientation that Western industrial models largely lack. Knowledge flows across the organisation rather than being held at the top. Workers on the factory floor are expected to understand and improve the process they are part of, not merely execute it. Suppliers are treated as part of the system, integrated early, given visibility into design decisions, expected to contribute to improvement. The whole supply chain is understood as a single system whose performance is determined by its weakest interdependency, not its strongest node.

The foundation of all of this is a belief about people. Not an abstract belief — a structural one, embedded in how roles are designed, how training works, how information flows. The belief is that the people closest to the work are the people most capable of improving it, if they are given the understanding and the authority to do so. This sounds obvious stated plainly. It is almost entirely absent from Western organisational design, which treats workers as executors of processes designed elsewhere, and reserves systemic understanding for a specialist class — the engineers, the architects, the consultants — who are paid to think about the whole while everyone else is paid to operate their part of it.

When knowledge is treated as infrastructure, it starts with this: the recognition that the people in the system are not inputs to be optimised but nodes in a network that improves when they can see what they are part of. You cannot build distributed systemic capability without first deciding that the people doing the work are worth investing in as thinkers, not just as operators. That decision has consequences that compound. A worker who understands the system catches failures before they propagate. A supplier who understands the design contributes improvements the designer didn’t anticipate. An organisation where understanding is shared laterally builds collective intelligence that no individual, however brilliant, can replicate alone.

But this only works if the organisation can hold two kinds of thinking at once. Systems thinkers see the network — the feedback loops, the dependencies, the second-order effects. Linear thinkers see the path — the sequence, the deliverable, the next step. Both are load-bearing. The failure mode is not having too much of one and not enough of the other. It is when each side reads the other’s strengths as incompetence. The systems thinker looks like they can’t commit. The linear thinker looks like they can’t see. Trust collapses, the network fragments, and the collective intelligence the organisation could have built never materialises. You end up with brilliant individuals producing worse outcomes than smaller teams that learned to translate between the two.

The Toyota Production System is the canonical example, but it is worth being specific about what made it different. It wasn’t efficiency for its own sake. It was the idea that every person in the system should be able to see the whole system well enough to identify waste and stop the line when something was wrong. That is a radical epistemological commitment — to distributed systemic understanding as the basis of quality — embedded directly into operational practice. Western manufacturing, by contrast, separated the people who understood the system (engineers, managers) from the people who operated it (workers), and then wondered why quality was harder to sustain.

The West calls it cheap. When Japanese electronics and automobiles began entering Western markets in the 1970s and 80s, the dominant interpretation was cost. Japanese goods were cheaper because Japanese labour was cheaper, because Japanese standards were lower, because Japan was a developing economy catching up with the West by cutting corners it could not afford. This interpretation was not entirely wrong — labour costs were a factor — but it was structurally convenient, because it required no examination of method. If they are cheap, we don’t have to ask whether they are doing something we are not.

The quality data eventually became impossible to ignore. Toyota’s defect rates were not just lower — they were an order of magnitude lower than American and European equivalents. Japanese consumer electronics did not just undercut Western products on price; they outperformed them on reliability. The explanation shifted: intellectual property theft, currency manipulation, state subsidy. Some of these were real factors. None of them fully accounted for the capability gap. But each successive explanation had the same function — preserving the narrative that the Western model was fundamentally sound and the competition was winning on illegitimate grounds.

Eastern capability compounds. What the West consistently underestimated was the rate at which distributed, systemic capability improvement accumulates over time. When knowledge is treated as infrastructure — shared across the organisation, built into processes, accessible to the people doing the work — it improves continuously and composes. Each improvement in one part of the system creates the conditions for improvement in adjacent parts. Taiwan’s semiconductor ecosystem is one illustration: TSMC did not just become the world’s leading chip manufacturer by building one good fab. It built an ecosystem of suppliers, toolmakers, process engineers, and research institutions, each specialised, each deeply integrated with the others, each improving continuously in ways that compound across the whole. The result is a capability that Western firms — despite spending far more on individual research programmes — have not been able to replicate, because replication requires the ecosystem, not just the factory.

China’s industrial trajectory makes the compounding dynamic even harder to dismiss. The West spent two decades treating China as a low-cost assembly location — a node in a supply chain, useful for its labour costs, not a source of systemic capability. That interpretation is now visibly wrong. In electric vehicles, China did not just build cheaper cars; it built an integrated ecosystem — battery chemistry, cell manufacturing, pack engineering, charging infrastructure, software, and vehicle design — simultaneously and in coordination, moving from negligible market share to global dominance in under fifteen years. In solar manufacturing, it achieved such comprehensive control of the supply chain that Western attempts to build domestic alternatives have struggled to compete on cost even with substantial state subsidy. In consumer electronics, drone technology, high-speed rail — the pattern recurs. What looked like assembly became manufacturing. What looked like manufacturing became innovation. The capability compounded because the system was designed to compound it, and because the people in the system were treated as participants in improvement rather than executors of someone else’s design.

The West eventually chooses the Eastern models. Lean manufacturing was imported wholesale from Toyota in the 1980s and 90s — often implemented badly, reduced to cost-cutting rather than understood as a knowledge management philosophy, but imported nonetheless. Agile software development emerged directly from observations of Japanese product development practices and was formalised in the Agile Manifesto in 2001. Supply chain integration — the idea that your suppliers should be partners in design rather than interchangeable vendors — is now standard practice in automotive and aerospace, adopted after decades of watching integrated supply chains outperform fragmented ones. The iPhone is designed in California and manufactured in a supply chain that Apple does not own and could not replicate if it tried, because the systemic manufacturing capability required to build it at that quality and scale does not exist in the West.

Each adoption follows the same arc: dismissal, competition, crisis, partial emulation, institutional resistance, eventual normalisation — with the origin quietly edited out of the narrative. We do not teach Lean as “what Toyota knew that Detroit refused to learn”. We teach it as a management framework, deracinated from the epistemological commitment that made it work.

This is not a story about cultural superiority, and it is worth being precise about why. There are Western economies that have retained deep manufacturing capability, and they have done so not by accident but through structural choices that diverge sharply from the dominant Anglo-American model. Germany is the clearest example. The Mittelstand — the dense ecosystem of mid-sized, often family-owned manufacturers that forms the backbone of the German economy — represents something the rest of the West largely failed to build or keep: companies with generational time horizons, deep process knowledge embedded in the workforce, apprenticeship systems that treat skilled trades as a legitimate career rather than a consolation prize, and a financial system oriented toward long-term industrial investment rather than quarterly returns. Germany did not offshore its manufacturing base in pursuit of shareholder value, because the institutional structures that would have rewarded that decision were weaker than the ones that rewarded capability retention. The result is a country that remains one of the world’s leading exporters of high-value manufactured goods, not because of natural resources or cheap labour, but because systemic knowledge was treated as worth keeping.

Eastern institutions have their own structural pathologies, and it is worth being specific rather than gesturing at balance.

Japan’s Lost Decade was partly a systems failure of a different kind. A corporate culture so oriented toward consensus and the avoidance of visible failure that it could not restructure when conditions changed. The same seniority systems that embedded long-term knowledge retention made it structurally difficult to challenge decisions from the top, or to adapt when the system’s assumptions proved wrong.

South Korea’s chaebol model — enormously effective at scaling industrial capability — produced conglomerates so large and politically entangled that they became too important to discipline. Corruption, suppressed competition, and concentrated risk followed.

China’s state coordination that enabled rapid industrial compounding also produces information environments where bad news travels slowly upward. Local officials optimise for reported metrics rather than underlying reality. Systemic risks accumulate quietly until they cannot be ignored. Though this is common in the West.

And across the region, educational systems that emphasise rote learning and deference to authority have their own version of the linearity problem — producing people who are exceptionally good at executing within defined systems, and less comfortable challenging the assumptions of those systems from the outside. And the West is not monolithic: Germany’s Mittelstand, Denmark’s wind energy supply chain, the aerospace clusters around Toulouse and Hamburg are all evidence that different institutional incentives produce different outcomes — that the hollowing out is a choice, not a civilisational destiny. But the recurring dynamic, repeated across industries and decades, is itself a systems story. Where the dominant Anglo-American model has prevailed — shareholder primacy, bottleneck economics, knowledge as private capital — the pattern holds. The West builds deep at the centre and loses capability at the edges. The East builds across the system and loses adaptability at the boundaries. Both dismiss what the other does well. The West dismisses, competes, emulates, claims the method as its own. And then, given enough institutional forgetting, does it again.

The irony is that the response is itself deeply linear. More funding programmes with defined deliverables. More compliance frameworks and reporting requirements. More committees to oversee committees. The insight — that distributed, compounding, people-centred systems outperform centralised and fragmented ones — arrives at the policy level and gets implemented as a procurement process. The form of the intervention contradicts the understanding that motivated it. Which is, by this point in the essay, exactly what you would expect.

Two Fundamentally Different Things

Across every domain this essay has moved through — education, hierarchy, infrastructure, knowledge, industrial policy — the same underlying difference keeps reappearing. It is worth naming it plainly.

Linear-based structures manage complexity by building layers of abstraction between their different types of linearity.

Systems-based structures manage complexity by allowing multiple truths and multiple layers to coexist simultaneously.

These are not different points on a spectrum. They are different beliefs about what complexity is for.

In practice, the linear model looks like this: the child cannot see the curriculum design, only the lesson. The worker cannot see the org chart, only their manager. The consumer cannot see the supply chain, only the product. The citizen cannot see the policy mechanism, only the service. Each layer simplifies what is below it, making it legible and controllable to the layer above. Nobody at any given level needs to hold the whole in mind, because the whole has been deliberately divided into parts that don’t require it.

The systems model looks like this: the worker sees the process and the system the process sits within. The supplier understands the design and its downstream consequences. The knowledge that was hidden behind an abstraction layer is instead made available — not to create chaos, but because the system improves when more nodes can see more of it. Complexity is not managed by hiding it. It is managed by distributing the capacity to understand it.

Everything else follows from this distinction. The pathologising of non-linear thinkers. The hoarding of systemic knowledge. The bottleneck economics. The policy responses that replicate the problem they are trying to solve. These are not separate failures — they are the same failure, expressed at different scales, by structures that can only conceive of one thing happening at a time.

The Trust Collapse

Here is the failure mode that everything else feeds into, and the one I find most important to name precisely:

Linear societies cannot build trust with people who think and perceive fundamentally differently. And without that trust, systems that require distributed, relational thinking cannot be built or maintained at scale.

This is more than cultural friction. It’s an epistemic problem. When your model of cognition is essentially universal — we all basically think in sequences, processes vary but structure is shared — you have no framework for encountering someone who is building a fundamentally different internal representation. Not thinking slowly or thinking fast, not being cautious or bold, but actually constructing reality relationally and spatially rather than linearly and temporally.

When a systems thinker says “this won’t scale” or “this creates a dependency you haven’t modelled,” the linear thinker doesn’t just disagree. They experience the statement as either arrogance or anxiety — because within their model of cognition, raising systemic concerns that nobody else can see is either grandstanding or catastrophising. The content of the statement cannot be correctly parsed because the cognitive mode that generated it isn’t legible.

This breaks trust. And when trust breaks between people who need to collaborate on complex problems, the collaboration defaults to the path of least resistance: simple, linear, controllable structures. Which is exactly what can’t handle the complexity. The failure becomes self-fulfilling.

The practical consequence is that large-scale systems — the kind that genuinely require distributed intelligence, feedback loops, and emergent coordination — are systematically under-built in Western contexts, or they are built by small groups of unusually aligned people who somehow found each other despite the structural obstacles. The Internet. Open source. The spaces where real distributed systems thinking has happened. Look at how anomalous they are. Look at how hard the surrounding structures have tried to absorb and monetise them.

What This Means

The problem isn’t that Western culture lacks smart people. It isn’t that systems thinking is inherently rare or hard. It’s that the structures — educational, organisational, economic, infrastructural — are comprehensively aligned against it. And that alignment is not accidental. It reflects a deep, mostly unexamined belief about what complexity is for.

Linear-based structures build layers of abstraction between their different types of linearity. Complexity is hidden, divided, controlled. One thing at a time. One layer at a time. One decision-maker at a time.

Systems-based structures allow multiple truths and multiple layers to occur at once. Complexity is shared, distributed, engaged with directly. Many things simultaneously. Many nodes with visibility. Many people equipped to understand what they are part of.

Western culture has overwhelmingly chosen the first. It has built its institutions, its incentives, its education systems, and its trust structures around it. And then struggled, repeatedly, to understand why complex problems keep defeating it.

Changing this is not a matter of better tools or training courses. But before we can talk about what to do, we need to understand why it keeps failing — specifically, why the trust between linear and systems thinkers breaks down so reliably.

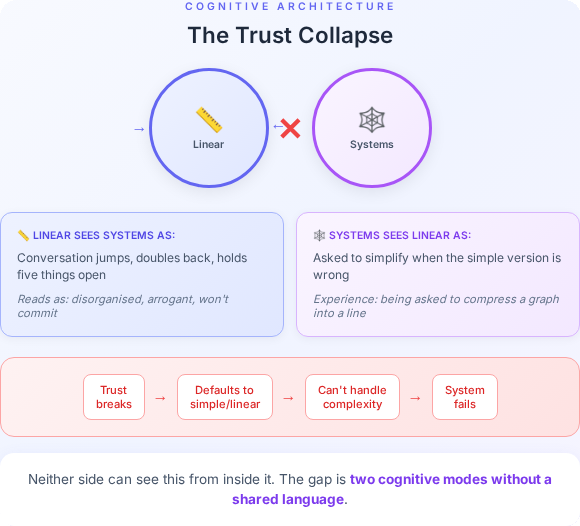

The breakdown is not personality. It is cognitive overload in both directions.

For the linear thinker, encountering a systems thinker in full flow is genuinely disorienting. The conversation doesn’t follow a path — it jumps, doubles back, holds five things open simultaneously, refuses to reach a conclusion before all the dependencies have been named. This is not how linear cognition processes information. It is exhausting and illegible. The natural response is to read it as disorganisation, or arrogance, or an unwillingness to commit. None of those interpretations are correct. But they feel correct, because the cognitive style producing the behaviour is invisible.

For the systems thinker, the reverse is equally true. Being asked to simplify, to get to the point, to stop raising problems and start proposing solutions — when you can see that the simple version is wrong and the proposed solution will break in three places you’ve already identified — is its own form of overload. It is the experience of being asked to compress a graph into a line, and then being evaluated on the quality of the line. The frustration is structural, not temperamental. But it reads as obstruction.

Neither side can easily see this from inside it. The linear thinker is not being closed-minded — they are processing at capacity. The systems thinker is not being difficult — they are trying to prevent a failure the other person cannot yet see. The trust gap is the product of two cognitive modes encountering each other without a shared language for what is actually happening.

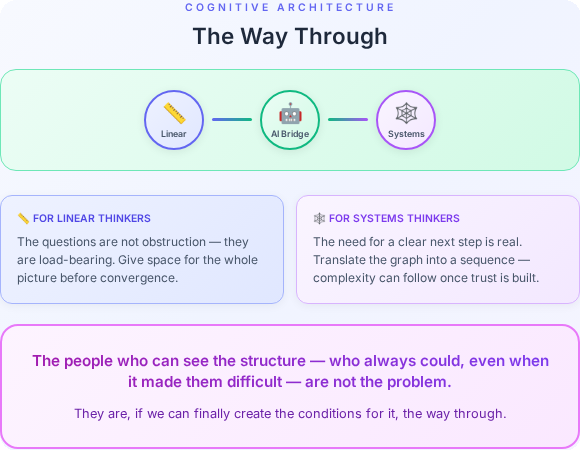

What helps is patience built on understanding — and understanding built on slowing down enough to ask what the other person is actually doing.

For linear thinkers working with systems thinkers: the questions are not obstruction. They are load-bearing. Give the systems thinker a defined space to surface the whole picture before forcing convergence. The efficiency cost upfront is real. The cost of skipping it tends to be larger, and arrives later.

For systems thinkers working with linear thinkers: the need for a clear next step is not intellectual laziness. It is how linear cognition builds confidence and moves forward. Translate the graph into a sequence — not because the sequence is the whole truth, but because it is the accessible entry point. The full complexity can follow once trust is established.

There is also something systems thinkers need to make peace with: layers of abstraction are not the enemy. They are necessary. For scale, for growth, for the freedom of choice that comes when complexity is made accessible to people who didn’t design it. The goal is not to eliminate abstraction — it is to build abstraction that is honest about what it hides, that can be inspected when needed, and that serves the people underneath it rather than concealing failure from them. A system built only for systems thinkers is not a system — it is an exclusive club. Building for everyone means building layers that different cognitive modes can enter at the level that works for them, without losing the integrity of what lies beneath.

This is what coaching each other actually looks like. Not one style capitulating to the other, but each developing enough fluency in the other’s mode to know when to adapt and when to hold ground.

Trust is not more regulation or defined processes. Trust is understanding why both modes are valid and absolutely needed for success.

And increasingly, we have a tool that can help with this in ways that weren’t available before.

AI — used well — can function as a cognitive bridge between different thinking styles. A systems thinker can use it to compress a complex model into a clear linear summary for a colleague who needs the sequence first. A linear thinker can use it to explore the wider implications of a decision they’ve made, surfacing the connections and dependencies they might not have seen. It can translate between modes in both directions — not replacing the thinking, but reducing the friction cost of communicating across cognitive difference. That is not a trivial capability. One of the most persistent costs of the trust gap between linear and systems thinkers is the sheer overhead of translation — the energy spent trying to make one mode legible to the other, which is exhausting for both sides and often fails anyway. Tools that reduce that overhead make genuine collaboration more accessible, not just for the cognitively privileged but for everyone trying to build something that actually works.

Which means it requires that people are not operating under chronic scarcity. Abstract encouragements to speak up land hollow when someone is one redundancy notice away from not being able to pay rent, heat their home, or put food on the table. The conditions for genuine cognitive collaboration are not just cultural — they are economic. Psychological safety is not a poster on a wall. It is what happens when people have enough stability — financial, social, physical — to bring their full thinking to a problem without first calculating what it might cost them.

None of this changes the deeper structural conditions overnight. Education, capital allocation, governance — these are slower and harder. But the trust work is available now, inside existing constraints, to anyone who has understood the problem well enough to want to solve it.

The linear structure cannot see itself as a structure. It can only see the path in front of it.

The people who can see it as a structure — who always could, even when that made them difficult — are not the problem. They are, if we can finally create the conditions for it, the way through.

Further Reading

Systems Thinking

Thinking in Systems — Donella Meadows — The essential primer on feedback loops and why fixing one part of a system often makes it worse.

Leverage Points — Meadows (free) — Short essay on where and how to actually change a system. The most useful thing she ever wrote.

The Fifth Discipline — Peter Senge — Applies systems thinking to organisations. The inability to see structure, not bad people, causes institutional failure.

The Knowledge-Creating Company — Nonaka & Takeuchi — How Japanese firms convert tacit knowledge into capability and why copying the surface practices doesn’t work.

Industrial Models

Toyota Production System — Taiichi Ohno — Primary source. Workers set standards, not managers. Distributed understanding as the basis for quality.

The New New Product Development Game — Takeuchi & Nonaka, HBR 1986 (free) — The paper that seeded Scrum. Parallel, self-organising teams vs sequential handovers.

Hidden Champions of the 21st Century — Hermann Simon — Germany’s Mittelstand firms: generational time horizons, deep knowledge retention, global niche dominance.

Out of the Crisis — W. Edwards Deming — The American whose ideas Japan adopted after WWII and the US ignored for 40 years. Quality as a systemic property.

East/West Industrial Divergence

Breakneck — Dan Wang — China as engineering state vs America’s lawyerly society. The clearest English-language account of how China’s industrial ecosystem works.

Dan Wang annual letters archive (free) — 2017–2023 letters on technology, manufacturing, and industrial ecosystems in China. Start here.

Chip War — Chris Miller — How the semiconductor industry became geographically concentrated and why you can’t fix it with procurement money.

Japan as Number One — Ezra Vogel — The 1979 book that first forced the West to take Japanese industrial organisation seriously.

Cognition & Education

Thinking in Pictures — Temple Grandin — Visual/spatial thinking as a complete cognitive mode, not a deficit. The clearest personal account of what the essay describes.

Neurodiversity in the Classroom — Thomas Armstrong — ADHD, dyslexia, autism as evolved cognitive profiles that linear classrooms systematically disadvantage.

Upside-Down Brilliance — Linda Silverman — Why spatial thinkers score well on IQ tests but poorly in school, and what that gap means.

Trust & Collaboration

The Fearless Organization — Amy Edmondson — The rigorous research base for psychological safety. High-performing teams surface errors; hierarchies suppress information.

Rebel Ideas — Matthew Syed — Cognitively homogeneous teams produce locally coherent, globally brittle thinking. Case studies from aviation to intelligence failures.

Cultures and Organizations — Geert Hofstede — Empirical data on power distance, long-term orientation, and individualism across cultures.

Political Economy

The Entrepreneurial State — Mariana Mazzucato — The internet, GPS, and touchscreens were publicly funded. Challenges the Western story of private sector innovation.

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital — Carlota Perez — Why Western policy responses to industrial challenges tend to be one paradigm late.

Brain of the Firm — Stafford Beer — Dense but foundational. The most rigorous framework for how organisations need to be structured to handle complexity.

AI as Cognitive Bridge

Co-Intelligence — Ethan Mollick — Practical and empirical on using AI as a genuine cognitive collaborator. Where it helps most is synthesis across domains.