Are Neurodivergents Just Resistant to Conditioning?

The numbers are going up. But what if that’s not the problem — what if the problem is what the numbers are measuring?

“Because It Is”

When I was at school, I asked a lot of questions. Not to be difficult — because I genuinely needed to understand why. Why are we doing it this way? What’s the reasoning behind this rule? How does this connect to the thing we learnt last week?

The answer I got, over and over, was some version of: because it is. Because that’s the rule. Because I said so. Because that’s how we do things here.

And when “because it is” wasn’t enough for me — when I pushed back, when I asked again, when I tried to find the logic underneath the instruction — I wasn’t given better tools to understand. I was told I was rude. Argumentative. Disruptive. The message was clear: the problem isn’t the answer. The problem is you, for not accepting it.

School was hierarchical, not fluid. Knowledge flowed one way — downward — and questioning that flow was treated as defiance rather than curiosity. There was no accommodation for the fact that my brain didn’t learn in straight lines. I learned in connections, in patterns, in why does this work rather than memorise that it works. But nobody was interested in how I learned. They were interested in whether I complied.

So I learned to comply. Or at least, I learned to try.

I went through my teenage years genuinely believing something was wrong with me. That everyone else could just fall in line and I couldn’t, and that gap was my failure. I was diagnosed with anxiety and depression — which, to be fair, I did have. But they were symptoms, not root causes. Nobody thought to ask why a kid who was clearly bright, clearly engaged, clearly thinking, was also clearly struggling. The answer was always medication and management. Never understanding.

It took me most of my twenties to undo that conditioning. To stop seeing my brain as the problem and start seeing it as a skill — as a gift, even, once I cleared out the noise. And there was a lot of noise to clear. I had to strip away the toxic consumerism I’d used to cope — the tv shows, the movies, the alcohol, the endless scroll through Instagram and Facebook, the numbing agents that the world hands you when it doesn’t want you to think too clearly. Because that’s what those things are, when you look at them honestly: tools for not thinking. Tools for not questioning the system. Tools for not questioning why the people who say they have your best interests at heart are the same ones telling you that you’re the one who needs to change.

It wasn’t. The thinking was never the problem.

But it took me a very long time to believe that. And I know I’m not the only one.

The Numbers

Let’s look at the data, because the data is genuinely staggering.

NHS England estimates that 2.5 million people in England have ADHD — and that includes those without a formal diagnosis. As of September 2025, up to 700,000 people were waiting for an ADHD assessment, with around six in ten having been on the waiting list for over a year. In some parts of the UK, waiting times have stretched to 10 to 15 years. ADHD was the second most viewed health condition on the NHS website in 2023, after COVID-19, with 4.3 million page views. People are searching for answers the system isn’t providing.

Autism tells a similar story. There are at least 700,000 diagnosed autistic people in the UK — more than 1 in 100. But a Lancet study using English primary care data estimated that between 59% and 72% of autistic people in England are undiagnosed, pushing the true number to potentially 1.2 million in England alone. Between 1998 and 2018, autism diagnosis incidence in the UK showed a 787% increase, with the sharpest rise among adults and women. As of March 2025, over 224,000 people were sitting on open referrals for suspected autism through the NHS, with 90% waiting longer than the recommended 13 weeks.

And these conditions don’t exist in isolation. NHS data shows that over 21% of autistic adults without a learning disability also have an ADHD diagnosis — and that number climbs every year. AuDHD — combined autism and ADHD — is increasingly recognised as its own distinct cognitive profile, not just a comorbidity but a way of experiencing the world.

The picture is similar in the US: the CDC’s latest figures show 1 in 31 children identified with autism by age eight, up from 1 in 150 in 2000. Around 11.4% of US children have received an ADHD diagnosis. The pattern is consistent across the English-speaking world: the numbers are accelerating.

So what’s going on? Is something “wrong” with more and more people? Or is something wrong with the systems those people are being measured against?

The Standard Explanation (And Why It’s Incomplete)

The mainstream narrative goes something like this: we’ve got better at diagnosing. Criteria have broadened. Awareness has increased. Social media has helped people recognise symptoms in themselves.

And all of that is true. The DSM-5 in 2013 allowed autism and ADHD to coexist as diagnoses for the first time — previously, you could only have one. That single change immediately captured a population that had been structurally excluded from identification. Women are finally being assessed rather than just told they’re anxious. Adults are realising that what they thought was a character flaw has a name. In 2024, NHS England launched its first dedicated ADHD taskforce — decades after the condition was formally recognised.

But here’s the thing: better diagnostic criteria don’t fully explain a 787% increase in UK autism diagnoses over twenty years. They don’t explain why only 1 in 9 adults with ADHD in the UK actually have a formal diagnosis. And they certainly don’t explain why so many of these individuals share a particular cognitive profile — one that looks suspiciously like it was designed to resist the very systems that are trying to categorise it.

The Cognitive Profile Nobody Talks About

Here’s what research consistently shows about neurodivergent minds, and what anyone who is neurodivergent already knows:

Systems thinking. Autistic individuals demonstrate a natural inclination towards understanding how things connect, how patterns form, how complex systems operate. Not in a linear, step-by-step way — in a web. In a network. They see the whole architecture while everyone else is focused on the current step in the process.

Divergent thinking. Research from the University of Amsterdam found that ADHD symptoms strongly predict divergent thinking ability — fluency, flexibility, and originality. The ADHD brain doesn’t follow the expected path because it’s already exploring five alternative paths simultaneously.

Pattern recognition. Studies on autistic perceptual processing show that autistic individuals often outperform neurotypical peers in identifying irregularities in complex data sets, detecting patterns others miss, and processing information with remarkable fidelity and detail.

Critical questioning. This is the one that doesn’t show up in the formal research as neatly, because it’s harder to measure. But spend five minutes in any neurodivergent community and you’ll hear it: Why are we doing it this way? Who decided this was the rule? What evidence supports this being the right approach?

These aren’t deficits. These are features. And they share a common thread: they all make you fundamentally difficult to condition.

And here’s the bitter irony: when neurodivergent people use these skills — when they connect dots, see the pattern, arrive at the insight — they’re met with disbelief. The refusal to accept that someone could have seen this without following the approved linear process. You can’t have just known that. Where’s the research? Who told you? Show your working. As if insight that arrives through pattern recognition and systems thinking is somehow less valid than insight that crawled through a peer-reviewed pipeline. The very ability that makes neurodivergent minds valuable is the one that gets dismissed, because the majority of people, they are the ones doing the dismissing, as they only trust knowledge that arrived the way their brains process it. The inability to trust anything other than linear research isn’t rigour, it’s a bottleneck. It’s a limitation dressed up as a standard.

So you try to show them. You lay it out. But because it doesn't arrive in a linear format — because the connections are lateral, because the reasoning jumps between layers of abstraction — it doesn't land. And neither side knows how to bridge that gap. They don't tell you what they need to process it — "walk me through this step by step" or "can you bring this down a level" — and you don't know what level they're on, because nobody ever taught either of you how to communicate across cognitive styles. So the idea gets dismissed. And then, slowly, so do you. Your credibility. Your competence. Your right to have seen what you saw. And after enough rounds of that — after enough times of your intuition being right and watching it go nowhere — you stop trying. You go quiet. And the system calls that progress. They got you to comply. Yay.

What Do We Mean By Conditioning?

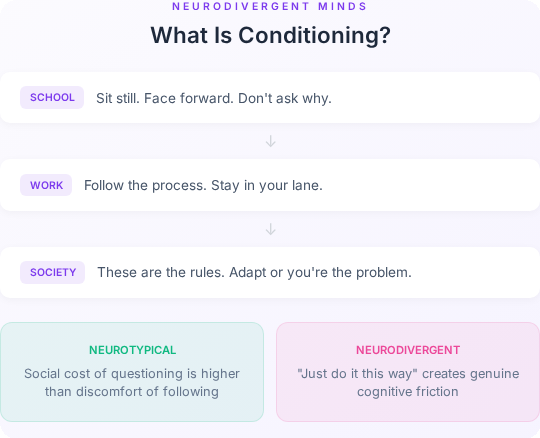

Conditioning is the process by which you learn to stop questioning and start complying. It starts in school: sit still, face forward, learn in this sequence, at this pace, in this way. Don’t ask why — that’s disruption. Don’t do it differently — that’s defiance. Don’t challenge the teacher — that’s a behaviour problem.

Then it continues at work: follow the process, respect the hierarchy, don’t question the decision, stay in your lane. We’ve always done it this way. That’s above your pay grade. You need to learn to pick your battles.

And it extends into society: these are the rules. This is how things work. These are the norms. If you can’t adapt to them, the problem is you.

For neurotypical brains — or at least, for brains that are more susceptible to social conditioning — this works. Not because the rules are correct, but because the social cost of questioning them is higher than the cognitive discomfort of following them. The conditioning succeeds because compliance is genuinely easier than resistance.

But neurodivergent brains don’t experience that trade-off the same way.

When you think in systems, you can’t unsee the broken system. When your brain naturally generates alternative approaches, being told “just do it this way” creates genuine cognitive friction. When you process the world in high fidelity, the gap between what is claimed and what is actually happening is painfully obvious.

The neurodivergent person isn’t being difficult. They’re being accurate. And the system has never known what to do with that.

The Lifetime of Being Told You’re Wrong

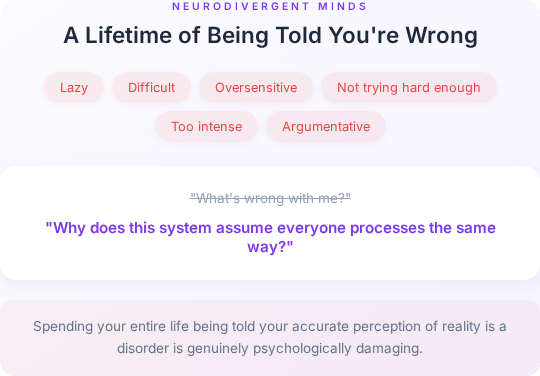

This is where it gets painful, and where the real damage is done.

If you’re a systems thinker who’s told from age five that the system is fine and you’re the problem, you don’t stop being a systems thinker. You just learn to mask it. You develop an elaborate performance of compliance while your internal world runs a constant parallel track of this doesn’t make sense, this isn’t working, this could be better, why won’t anyone listen?

This is what high masking looks like. And the cost of it is enormous.

The mental health statistics for neurodivergent individuals aren’t high because neurodivergence is inherently associated with poor mental health. They’re high because spending your entire life being told that your accurate perception of reality is a disorder is genuinely psychologically damaging. Imagine being right about how the system works and spending forty years being medicated, therapised, and performance-managed for saying so.

Late-diagnosed adults — and there are millions of them — often describe the same experience: decades of knowing something was different, being told they were lazy, difficult, oversensitive, not trying hard enough, too intense. And then the diagnosis arrives, and suddenly their entire life makes sense. Not because the label fixes anything, but because it reframes the question. It was never “what’s wrong with me?” It was always “why does this system assume everyone processes the same way?”

The Rules Are Made Up

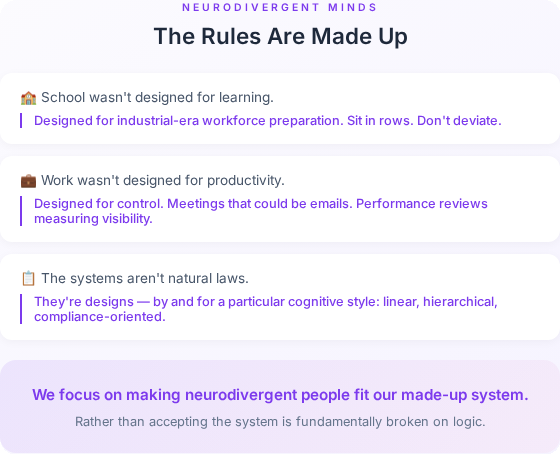

Here’s the part that’s becoming increasingly difficult to ignore: the rules actually are made up.

Not in a nihilistic sense. In a structural sense. The way we organise work, education, social interaction, economic participation — these aren’t natural laws. They’re designs. And they were designed, largely, by and for a particular cognitive style: linear, hierarchical, compliance-oriented, socially conformist.

And it’s worth being precise about this: it’s not that most people in Western societies think linearly. It’s that most Western institutions are structured linearly. Education, law, science, corporate management, governance — all built on frameworks that emerged from the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, all prioritising sequential reasoning, cause-and-effect chains, hierarchical authority, and reductionism. Many non-Western knowledge traditions — Indigenous, East Asian, various African philosophical frameworks — have historically been far more systems-oriented, more circular, more comfortable holding multiple truths simultaneously. Western academic culture has often dismissed these as “less rigorous” when they’re actually just non-linear. So Western societies don’t think linearly so much as they reward linear thinking and punish everything else. Which is conditioning, again.

School wasn’t designed for learning. It was designed for industrial-era workforce preparation. Sit in rows. Follow instructions. Don’t deviate. The bell tells you when to start and stop. Your value is measured by your ability to reproduce information in a standardised format under timed conditions.

Work wasn’t designed for productivity. It was designed for control. Open-plan offices, nine-to-five schedules, meetings that could have been emails, performance reviews that measure visibility rather than output — none of this is optimised for actually getting things done. It’s optimised for compliance.

We focus our efforts on making neurodivergent people fit into our made-up system and our made-up rules, rather than accepting that our made-up system and made-up rules are fundamentally broken on logic.

And the neurodivergent brain, which was never built for compliance in the first place, experiences all of this as friction. Not because it can’t do the work — often it can do the work better, faster, and more creatively when it comes to systemic problems. But because the work is wrapped in an arbitrary set of social performance requirements that serve no functional purpose.

The Rise Isn’t a Crisis. It’s a Correction.

So when we see the numbers climbing — 1 in 31 for autism, 11.4% for ADHD, an estimated 15–20% of the global population showing some form of neurodivergence — the question shouldn’t be “what’s causing this epidemic?”

The question should be: what changed to make identification possible, and what does it mean that so many people were invisible for so long?

What changed is that information became decentralised. The internet, and particularly social media, broke the conditioning pipeline. People started comparing experiences. They started realising that the thing they’d been told was a personal failing was actually a shared neurological profile. They started asking questions — the one thing the system was designed to prevent.

And now we’re in an awkward moment where the numbers are undeniable but the implications are uncomfortable. Because if 15–20% of the population genuinely thinks differently — in systems, in patterns, in webs rather than lines — then the problem isn’t that one in five people is broken.

The problem is that the remaining four out of five built a world that only works for them, and called it normal.

What Comes Next

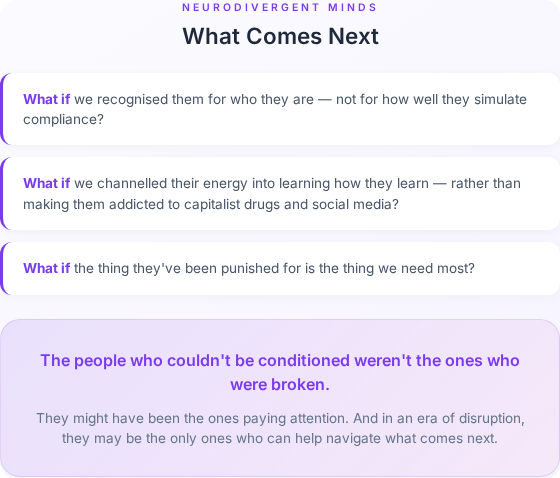

I’m not arguing that neurodivergence is a superpower. That framing is its own kind of conditioning — it says you’re only valuable if your difference can be monetised. Plenty of neurodivergent people struggle profoundly, and that struggle is real and deserves support.

What I am arguing is that the framing of neurodivergence as disorder — as deviation from a healthy norm — is itself a product of the conditioning that neurodivergent minds naturally resist. And as the numbers grow, and as more people refuse to mask, and as the systems that were built on compliance continue to fail at scale, we might have to accept something uncomfortable:

The people who couldn’t be conditioned weren’t the ones who were broken.

They might have been the ones paying attention.

And in a new era of disruption — where AI is reshaping work, where institutions are losing trust, where the old playbooks are failing in real time — they may be the only ones who can help navigate what comes next. Because you don’t navigate disruption with compliance. You navigate it by thinking in systems, asking hard questions, and refusing to accept “because it is” as an answer.

What if we recognised them and accepted them for who they are — not for performative measures and metrics, not for how well they simulate compliance — and found ways to fully realise their gifts and unique capabilities, rather than forcing them to be medicated, silenced, and restricted?

What if we accepted that their ability to deviate and change directions isn’t chaotic, it’s understanding how new data and information drastically influences decisions. That the system is intentionally designed to be noisy.

What if we channelled their time and energy into learning and understanding themselves and the way they learn, rather than making them addicted to the latest capitalist drugs and social media, and calling that "free will"?

What if we accepted that some people genuinely think non-linearly and some more linearly — and that our education systems prioritise linear thinking not because it's better, it absolutely is for deep isolated research, but also because it's easier for them to monitor and control in a hierarchical system?

The very thing they have been punished their entire lives for, might be the thing we need most.

If this resonated, share it. If it made you uncomfortable, sit with that. Both responses are data.

Sources

UK ADHD Data

NHS England ADHD Management Information (November 2025) — 2.5 million estimated with ADHD in England; up to 700,000 waiting for assessment

House of Commons Library: FAQ on ADHD Statistics (England) — waiting list breakdowns, only 1 in 9 adults with ADHD formally diagnosed

NHS England: Report of the Independent ADHD Taskforce (Part 1) — 10–15 year waiting times in some areas; only 25% of children and 15% of adults with ADHD receiving treatment

NHS Digital: Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (England 2023/24) — Chapter 9: ADHD — ADHD as second most viewed NHS condition; screening and service use data

ADHD UK: Diagnosis Rate Statistics — prescription trends, private vs NHS, regional variation

UK Autism Data

O’Nions et al. (2023) — Autism in England: Assessing Underdiagnosis (The Lancet Regional Health – Europe) — 59–72% of autistic people in England potentially undiagnosed; true number may exceed 1.2 million; 787% increase in diagnosis incidence 1998–2018

NHS England: Autism Waiting Time Statistics (April 2024 to March 2025) — 224,000 open referrals; 90% waiting longer than 13 weeks

NHS Digital: Health and Care of People with Learning Disabilities (2024–25) — 21.6% of autistic adults without learning disability also diagnosed ADHD; diagnosis rates rising year on year

National Autistic Society: What Is Autism — at least 700,000 autistic people in the UK

US Data (Supporting Context)

CDC: Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder (May 2025) — 1 in 31 children (3.2%) identified with ASD

Shaw et al. (2025) — Prevalence and Early Identification of Autism, MMWR Surveillance Summaries — full ADDM Network data across 16 sites

Qbtech: Understanding ADHD in 2025 — 7.1 million US children with ADHD diagnosis (11.4%)

Neurodivergent Cognition and Strengths

Boot et al. (2022) — Characterizing Creative Thinking and Creative Achievements in Relation to ADHD and ASD Symptoms (Frontiers in Psychiatry / PMC) — ADHD symptoms predict divergent thinking (fluency, flexibility, originality)

Mottron et al. (2006) — Enhanced Perceptual Processing in Autism — autistic individuals outperform neurotypical peers in pattern recognition and visual discrimination

The Neurodivergent Brain: Introduction to Systems Thinking in Autism — autistic inclination towards systems thinking

Kaaria et al. (2025) — The Role of Neurodiversity in Enhancing Decision-Making Processes (ResearchGate) — neurodiverse teams enhance creativity, critical thinking, and risk assessment

NALA: The Power of Thinking Differently — Neurodiversity and Problem Solving — 15–20% of global population neurodivergent; Stanford Neurodiversity Project

Western Linear Thinking vs Non-Western Knowledge Systems

Mazzocchi (2006) — Western Science and Traditional Knowledge (EMBO Reports / PMC) — traditional knowledge systems “do not interpret reality on the basis of a linear conception of cause and effect, but rather as a world made up of constantly forming multidimensional cycles”

Yama & Zakaria (2019) — Explanations for Cultural Differences in Thinking: Easterners’ Dialectical Thinking and Westerners’ Linear Thinking (Journal of Cognitive Psychology) — Western linear thinking rooted in ancient Greek logic; Eastern dialectical thinking rooted in Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism

Association of Commonwealth Universities: Hierarchies of Knowing — how Western knowledge systems dominate globally, pushing non-Western ways of knowing to the margins

Turner et al. (2024) — An Organizing Framework to Break Down Western-Centric Views of Knowledge in North–South Research (Sustainability Science / PMC) — Western-centric approaches fail to recognise diverse worldviews and knowledge systems